OD

Levi Horn played football for the NFL, and before that for the University of Montana. But before that, he played for Rogers High School in the Hillyard neighborhood in Spokane.

Football at Rogers, and the people around him there, set him on a good path, he says. That was even as he struggled with his family’s experience with addiction and a friend’s opioid overdose death.

“The game has taught me to receive help and ask for help,” Levi says.

After the NFL, Levi returned to Rogers as a drug and alcohol counselor. Now studying to become a school counselor, he also shares his story and Northern Cheyenne culture with Native and other people throughout the U.S.

When Levi talks with kids about fentanyl, he tells them it’s commonly mixed in with other drugs — but you can’t see, taste, or smell it. He tells them a tiny amount can kill a person — but you can’t tell how much fentanyl is in the drug you might be using.

And he is among Native people spreading the word about naloxone — a “big word for Narcan.” Anyone can carry naloxone to reverse an opioid overdose. Anyone can use it. Anyone can save a life.

Teaching people how to help

Levi Horn played football for the NFL, and before that for the University of Montana. But before that, he played for Rogers High School in the Hillyard neighborhood in Spokane.

Football at Rogers, and the people around him there, set him on a good path, he says. That was even as he struggled with his family’s experience with addiction and a friend’s opioid overdose death.

“The game has taught me to receive help and ask for help,” Levi says.

After the NFL, Levi returned to Rogers as a drug and alcohol counselor. Now studying to become a school counselor, he also shares his story and Northern Cheyenne culture with Native and other people throughout the U.S.

When Levi talks with kids about fentanyl, he tells them it’s commonly mixed in with other drugs — but you can’t see, taste, or smell it. He tells them a tiny amount can kill a person — but you can’t tell how much fentanyl is in the drug you might be using.

And he is among Native people spreading the word about naloxone — a “big word for Narcan.” Anyone can carry naloxone to reverse an opioid overdose. Anyone can use it. Anyone can save a life.

Teaching people how to help

Fentanyl overdose can slow or stop your breathing. This prevents oxygen from reaching your brain, which can cause a coma or brain damage or kill you.

Naloxone, also called Narcan, can reverse a fentanyl overdose when it’s used in time. It saves lives. Many people are learning the signs of overdose and carrying naloxone. They’re ready to help if someone nearby needs it.

- Naloxone is simple to use.

- It’s available at no charge from many tribes and community organizations.

- Many people keep it at home, in their backpacks or purses, or at work.

Fentanyl overdose can slow or stop your breathing. This prevents oxygen from reaching your brain, which can cause a coma or brain damage or kill you.

Naloxone, also called Narcan, can reverse a fentanyl overdose when it’s used in time. It saves lives. Many people are learning the signs of overdose and carrying naloxone. They’re ready to help if someone nearby needs it.

- Naloxone is simple to use.

- It’s available at no charge from many tribes and community organizations.

- Many people keep it at home, in their backpacks or purses, or at work.

CHECK FOR SIGNS.

A person who’s overdosing on fentanyl might look asleep. Try to wake them. Listen to their breathing. Check their lips and fingernails. Signs of overdose: they don’t wake up; they’re not breathing normally; they’re making a gurgling sound; or their skin or nails are cool, blue, gray, or pale.

CALL 911.

If you can, stay with the person until help arrives. In most cases, Washington law protects you and the person who’s overdosing against drug-possession charges if you get help to save their life (there are exceptions). Many tribes have similar laws. To learn your tribe’s laws, ask your tribal health care center or police department.

GIVE THEM NALOXONE.

Naloxone should improve their breathing and wake them up. If you don’t see a response within two or three minutes, use another dose — sometimes it takes several doses. 911 responders can keep the person from overdosing again as the naloxone wears off. If you use multiple doses and nothing happens, it might not be an opioid overdose.

DO CPR.

If the person still isn’t breathing or doesn’t have a pulse, do chest compressions and rescue breaths. Chest compressions alone can help, even without breaths.

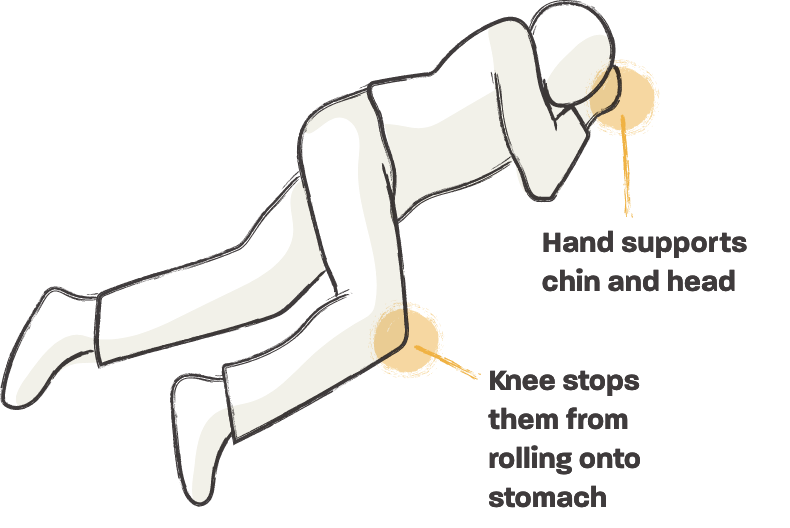

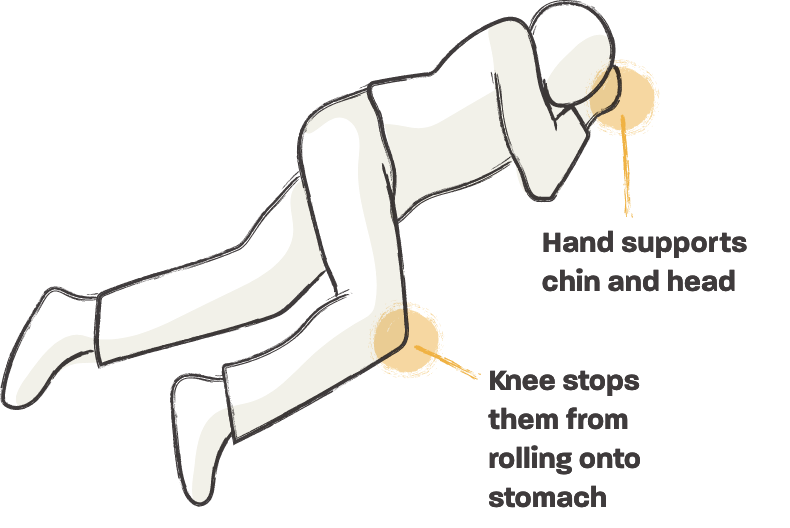

PUT THEM IN A RECOVERY POSITION AFTER THEY START BREATHING.

This helps prevent them from choking if they vomit.

CHECK FOR SIGNS.

A person who’s overdosing on fentanyl might look asleep. Try to wake them. Listen to their breathing. Check their lips and fingernails. Signs of overdose: they don’t wake up; they’re not breathing normally; they’re making a gurgling sound; or their skin or nails are cool, blue, gray, or pale.

CALL 911.

If you can, stay with the person until help arrives. In most cases, Washington law protects you and the person who’s overdosing against drug-possession charges if you get help to save their life (there are exceptions). Many tribes have similar laws. To learn your tribe’s laws, ask your tribal health care center or police department.

GIVE THEM NALOXONE.

Naloxone should improve their breathing and wake them up. If you don’t see a response within two or three minutes, use another dose — sometimes it takes several doses. 911 responders can keep the person from overdosing again as the naloxone wears off. If you use multiple doses and nothing happens, it might not be an opioid overdose.

DO CPR.

If the person still isn’t breathing or doesn’t have a pulse, do chest compressions and rescue breaths. Chest compressions alone can help, even without breaths.

PUT THEM IN A RECOVERY POSITION AFTER THEY START BREATHING.

This helps prevent them from choking if they vomit.

Naloxone, or Narcan, is simple to use. Here’s how to do it.

PUT THE DEVICE’S TIP IN THEIR NOSE. PRESS THE PLUNGER.

Naloxone can be injectable, but it’s often a nasal spray. If you think someone is overdosing, it is important to give them naloxone. Even if they haven't used opioids, it is OK for them to get naloxone.

- Open the box and packaging.

- Hold the tip of the nozzle inside either nostril.

- Press the plunger all the way (until it clicks).

- If you don’t see a response in two or three minutes, use another dose. Each device holds one dose. It may take several doses, but one or two usually works.

THEY COULD OVERDOSE AGAIN, SO TRY TO STAY WITH THEM.

When naloxone is used in time, the person should start breathing normally and wake up. Keep in mind:

- They could overdose again after the naloxone wears off, in about 30 to 90 minutes.

- It’s best to stay with them until 911 responders arrive.

- People might have withdrawal symptoms after getting naloxone. They might not remember what happened. They might be scared, nervous, or restless.

- If you can, help them stay calm and prevent them from taking more drugs.

Tribes often provide naloxone and training at no charge. Check with:

- Your tribe.

- Your pharmacy. You can buy naloxone at many pharmacies in Washington because of a statewide standing order that acts as a prescription. Discount cards like ArrayRx Card can help lower the price if you don’t have insurance. It can help to call the pharmacy ahead of time to make sure they have naloxone, and to take along a digital or printed copy of the standing order. (The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved over-the-counter naloxone nasal spray — meaning no prescription will be required — but it's not available yet.)

- Your local substance-prevention coalition.

- The Native Resource Hub at (866) 491-1683. The Hub helps Indigenous people in Washington find resources such as naloxone, as well as culturally appropriate care and services, including addiction treatment and recovery.

- This statewide naloxone finder tool.

- The People's Harm Reduction Alliance, where you can request free naloxone by mail in Washington. A limited supply of naloxone is available through this program for people with no other way to get it.

Tribes often provide naloxone and training at no charge. Check with:

- Your tribe.

- Your pharmacy. You can buy naloxone at many pharmacies in Washington because of a statewide standing order that acts as a prescription. Discount cards like ArrayRx Card can help lower the price if you don’t have insurance. It can help to call the pharmacy ahead of time to make sure they have naloxone, and to take along a digital or printed copy of the standing order. (The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved over-the-counter naloxone nasal spray — meaning no prescription will be required — but it's not available yet.)

- Your local substance-prevention coalition.

- The Native Resource Hub at (866) 491-1683. The Hub helps Indigenous people in Washington find resources such as naloxone, as well as culturally appropriate care and services, including addiction treatment and recovery.

- This statewide naloxone finder tool.

- The People's Harm Reduction Alliance, where you can request free naloxone by mail in Washington. A limited supply of naloxone is available through this program for people with no other way to get it.

Besides carrying naloxone, we can take other steps to reduce the risk of overdose or death from fentanyl.

- If you use, try not to do it alone. You can’t use naloxone on yourself if you overdose. Some people use resources like Never Use Alone, available 24/7. The people there can call 911 for you.

- Use test strips to help detect fentanyl laced into other drugs in different forms (pills, powders, injectables). Some harm-reduction programs, such as needle exchange programs, provide test strips. Check with your tribal or community health center, or call the Native Resource Hub at (866) 491-1683. You also can buy test strips online.

- Avoid mixing drugs, including mixing drugs with alcohol.

Offer care without judgment — it can make a big difference.

Here’s one more way to help. Talk with someone about their drug use without judgment, whether it’s with family or in community spaces. Caring about someone who uses drugs can be complicated. But stigma can stop us from supporting people and sharing information.

Besides carrying naloxone, we can take other steps to reduce the risk of overdose or death from fentanyl.

- If you use, try not to do it alone. You can’t use naloxone on yourself if you overdose. Some people use resources like Never Use Alone, available 24/7. The people there can call 911 for you.

- Use test strips to help detect fentanyl laced into other drugs in different forms (pills, powders, injectables). Some harm-reduction programs, such as needle exchange programs, provide test strips. Check with your tribal or community health center, or call the Native Resource Hub at (866) 491-1683. You also can buy test strips online.

- Avoid mixing drugs, including mixing drugs with alcohol.

Offer care without judgment — it can make a big difference.

Here’s one more way to help. Talk with someone about their drug use without judgment, whether it’s with family or in community spaces. Caring about someone who uses drugs can be complicated. But stigma can stop us from supporting people and sharing information.

START TALKING BY LISTENING.

- Everyone wants to be heard and understood. If you’re worried about a friend or family member, you might want to tell them what to do. Instead, hear them out.

- Try asking them about their experience. Ask about their support network, their thoughts about overdose risk, what they might need in order to consider treatment, what they might need during recovery, their worries about other people.

- Listen well. How you listen and respond to your relative or friend builds trust. It could help them open up to you later or ask for your support when they’re ready.

- Ask them about what they’re doing well. By talking about steps they’re already taking to protect themselves and be healthy, you can affirm and encourage their effort and success.